In 1824, General, The Marquis de Lafayette, returned to the United States. President Monroe, with a resolution from Congress, sent an invitation to Lafayette welcoming him back to the United States, along with financial assistance and a land grant in Florida. It was a heartfelt gesture that Lafayette accepted eagerly. He arrived in New York aboard the US frigate Cadmus and toured his way south towards the capital, eventually visiting all 24 states. Beginning with this post, we are going to look at various aspects of Lafayette’s life and beliefs in honor of the Bicentennial of his Return to the United States in 1824. In today’s post we are going to attempt to ask the question of whether Lafayette was/is a United States citizen, so come along as we explore this convoluted subject.

To begin with, very few people are aware that, following the American Revolution, several states, passed laws making Lafayette, and sometimes his family, citizens of their respective states. (Connecticut – 1784, Maryland – 1784, Virginia – 1785). In fact, this status of citizenship, also conferred upon his family by Connecticut, may well have saved the life of his wife during the French Revolution. In 1795, Lafayette’s wife, Adrienne, the Marquise de Lafayette was imprisoned and facing execution by the French Revolutionaries. Elizabeth Monroe, a future First Lady of the United States and wife to James Monroe, the United States envoy to France, intervened, attempting to save her. A 1919 New York Times article included a facsimile of the Maryland act, as well as a transcript of the text:

An Act to naturalize Major General the Marquiss de la Fayette and his Heirs Male Forever.

Be it enacted by the General Assembly of Maryland—that the Marquiss de la Fayette and his Heirs male forever shall be and they and each of them are hereby deemed adjudged and taken to be natural born Citizens of this State and shall henceforth be instilled to all the Immunities, Rights and Privileges of natural born Citizens thereof, they and every one of them conforming to the Constitution and Laws of this State in the Enjoyment and Exercise of such Immunities, Rights and Privileges.

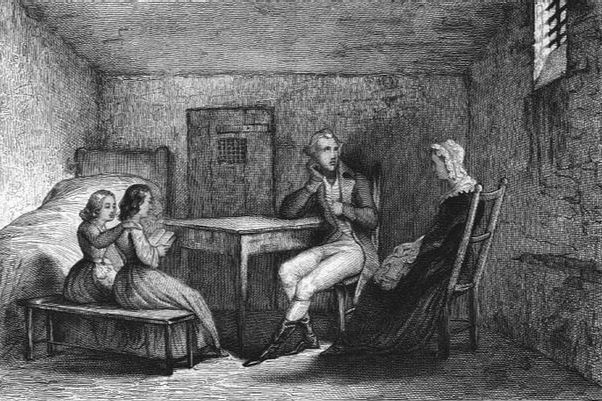

The day prior to Madame Lafayette's scheduled execution, Mrs. Monroe visited the imprisoned marquise and loudly announced that she would be returning the following day. Not wanting to endanger ties with the United States, France abruptly reversed its verdict and did not execute her. It has also been suggested, without any direct proof, that the Americans may have pressed the point that the Lafayettes were American citizens and executing the marquise would not be looked upon favorably by the United States. This suggestion is further supported by the fact that, after her release she and her children traveled to Hamburg, where the American consul issued passports to a “Mrs. Motier of Hartford, Connecticut,” which she used to travel to Vienna.

After her son, Georges Washington Lafayette, had been smuggled out of France and taken to the United States, Adrienne and her two daughters asked for, and received, an audience with Emperor Francis, who granted permission for the three women to live with Lafayette in captivity at Olmütz (today Olomouc in the Czech Republic) where her husband was incarcerated as a political prisoner. Lafayette, who had endured harsh solitary confinement since his escape attempt a year before, was astounded when soldiers opened his prison door to usher in his wife and daughters on 15 October 1795. The family spent the next two years in confinement together.

Another indication of their belief that they were American citizens is shown by Lafayette, when captured, had tried to use the American citizenship he had been granted to secure his release, and contacted William Short, United States minister in The Hague. Although Short and other U.S. envoys very much wanted to succor Lafayette for his services to their country, they knew that his status as a French officer took precedence over any claim to American citizenship. Additionally, Washington, who was by then president, had instructed the envoys to avoid actions that entangled the country in European affairs, and the U.S. did not have diplomatic relations with either Prussia or Austria. They did send money for the use of Lafayette, and for his wife. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson found a loophole allowing Lafayette to be paid, with interest, for his services as a major general from 1777 to 1783. An act was rushed through Congress and signed by President Washington. These funds allowed the Lafayettes to live with unusual privileges in their captivity.

Through diplomacy, the press, and personal appeals, Lafayette's sympathizers on both sides of the Atlantic made their influence felt, most importantly on the post-Reign of Terror French government. General Napoleon Bonaparte negotiated the release of the state prisoners at Olmütz, in the Treaty of Campo Formio and Lafayette's captivity, of over five years, ended. The Lafayette family left Olmütz under Austrian escort early on the morning of 19 September 1797, crossed the Bohemia-Saxony border north of Prague, and were officially turned over to the American consul in Hamburg on 4 October.

From all the above, we see that not only did Lafayette and his family believe they were American citizens but also that the US Government, recognized their citizenship, both under the Article of Confederation and under the US Constitution. However, as we see repeatedly, the US Government is likely to change their minds on things that everyone thought was decided and, in 1935 the US State Department revoked his citizenship. This was due to their interpretation of the US Constitution. According to their reading, being a citizen of a state did not convey automatic citizenship when the Articles of Confederation were replaced by the US Constitution.

The Constitution as originally adopted assumes that there is citizenship of the United States, and of the States, but does not explicitly provide a rule that tells whether anyone is a citizen of either (other than by giving Congress the power to naturalize). Article II provides that only a natural-born citizen of the United States, or a citizen of the United States at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, may be President, and thus assumes that some people have national citizenship. Nowhere, however, does the original Constitution lay down a clear and comprehensive rule about either kind of citizenship. Unfortunately, Lafayette, was not a resident of the United States at the time the Constitution was adopted, which, if he had been, would make this entire blog post a moot point.

In 1935, a State Department letter addressed the question of whether the citizenship conferred by the States could be interpreted to have ultimately resulted in the Marquis de Lafayette being a United States citizen. Their determination was that it DOD NOT. The State Department provided an excerpt from the Journals of the Continental Congress in 1784 which stated in the Congress' farewell to the Marquis that "as his uniform and unceasing attachment to this country has resembled that of a patriotic citizen of the United States . . . '' as proof that the citizenship was not considered to have translated to a federal level.

This was, at least partially, finally rectified. On August 7, 2002, the U.S. Congress posthumously made Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, an honorary citizen of the United States. Lafayette is only one of eight people to receive this honor, others include Winston Churchill and Mother Teresa, and one of only two to be made an honorary citizen by an act of Congress. The resolution, Public Law 107–209, acknowledged Lafayette's efforts on behalf of the United States and Liberty, and defined the symbolic gesture of honorary citizenship. Honorary citizenship does not grant additional legal rights or impose additional responsibilities, either in the United States or internationally.

The legislation reads:

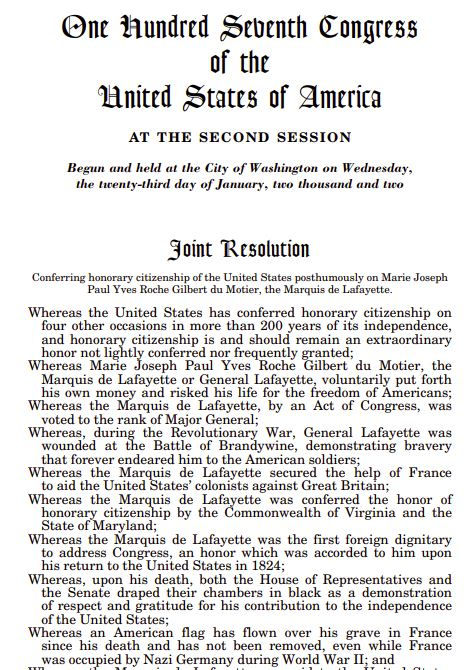

Joint Resolution

Conferring honorary citizenship of the United States posthumously on Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette.

Whereas the United States has conferred honorary citizenship on four other occasions in more than 200 years of its independence, and honorary citizenship is and should remain an extraordinary honor not lightly conferred nor frequently granted;

Whereas Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette or General Lafayette, voluntarily put forth his own money and risked his life for the freedom of Americans;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette, by an Act of Congress, was voted to the rank of Major General; Whereas, during the Revolutionary War, General Lafayette was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine, demonstrating bravery that forever endeared him to the American soldiers;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette secured the help of France to aid the United States’ colonists against Great Britain;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette was conferred the honor of honorary citizenship by the Commonwealth of Virginia and the State of Maryland;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette was the first foreign dignitary to address Congress, an honor which was accorded to him upon his return to the United States in 1824;

Whereas, upon his death, both the House of Representatives and the Senate draped their chambers in black as a demonstration of respect and gratitude for his contribution to the independence of the United States;

Whereas an American flag has flown over his grave in France since his death and has not been removed, even while France was occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II; and

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette gave aid to the United States in her time of need and is forever a symbol of freedom: Now, therefore be it

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, is proclaimed posthumously to be an honorary citizen of the United States of America.

So, as we can see, apparently, Lafayette and his family were considered citizens of the United States from its founding up until 1935. From 1935 until 2002 they had no citizenship status in the United States, and since 2002 Lafayette, but not his family, has been an Honorary Citizen of the United States.

We hope you enjoyed today's post, “The Marquis de Lafayette - U.S. Citizen or Not?” This is the first of three posts we will be putting up in honor of Lafayette’s 1824 visit to the Hampton Roads region of Virginia between now and the end of October. We hope this will interest you in learning more about the Marquis de Lafayette’s role in American History. Please join us again next month for a look into another aspect of the life of the Marquis de Lafayette and its effect on history both here and in France.

Until then, while you are here on our website, we would also encourage you to join our blog community (Look for the button in the upper right-hand corner of this post). This will allow us to inform you when we post new articles. We also suggest that you return to our blog home page and sample our other articles on a wide variety of late-18th and early-19th century subjects; both military and civilian.

Finally, if you live in Virginia, Maryland, or North Carolina, we invite you to visit The Norfolk Towne Assembly’s home page to learn more about us, what we do, and how you can get involved in our historic dance, public education, and living history efforts.

Resources

Appeals, B. O. (1955, October 7). Citizenship — Effect upon male descendants of Lafayette of the Maryland Act of 1784. Retrieved from casetext: https://casetext.com/admin-law/in-the-matter-of-m-22

Cloquet, M. J. (1835). Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette. London: Baldwin and Cradock.

Crawford, M. M. (1907). Madame de Lafayette and Her Family. New York: James Pott & Co.

Crow, M. F. (1916). Lafayette. New York: The MacMillan Company.

Folliard, E. T. (1973, May 25). JFK Slipped on Historical Data in Churchill Tribute. Sarasota Journal, pp. 12-F.

Gottschalk, L. R. (1950). Lafayette Between the American and the French Revolution (1783–1789). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lane, J. (2003). General and Madame de Lafayette. London: Taylor Publishing Company.

Sensenbrenner, J. F. (2002, July 19). House Report 107-595. Retrieved from govinfo.gov: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CRPT-107hrpt595/html/CRPT-107hrpt595.htm

Speare, M. E. (1919, September 7). "Lafayette, Citizen of America". New York Times.

Comments