Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette is perhaps most familiar to Americans as the dutiful teenage major general who served in the Continental Army under George Washington. However, he left another legacy, his stubborn push to end slavery and as an advocate for human rights and dignity. Inspired by the ideals of the Enlightenment, his friendship and service with African Americans during the Revolutionary War and his devotion to the ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence, his human rights work began in earnest soon after his military service in America and return to France.

Lafayette and Slavery

How and when Lafayette became an advocate for emancipation, we cannot be certain. One important influence was his friend and fellow soldier in the Continental Army, John Laurens from South Carolina. Although Laurens father was a slave owner in South Carolina, John was greatly influenced by Enlightenment ideas, and he spoke to Lafayette often about the evils of slavery and proposed (unsuccessfully) to grant the enslaved their freedom in exchange for military service.

Lafayette also became well acquainted with an enslaved soldier by the name of James Armistead, who volunteered to serve with Lafayette during the siege of Richmond in 1781. Later that year, Lafayette paid Armistead to spy on General George Cornwallis by posing as a fugitive. The information Armistead gathered was invaluable to the American and French forces and contributed to their victory at Yorktown. In appreciation, Lafayette helped Armistead win his freedom after the war.

Another major influence on Lafayette might have been, quite simply, the irony of fighting for freedom in a country where one-sixth of the population was enslaved. Lafayette was a man of logic and therefore unable and unwilling to accept such irony. Whatever the reason, however, Lafayette was not one to only talk but instead began putting together plans to move emancipation forward.

In 1783, during the closing days of the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette wrote his commander, friend and mentor, George Washington, suggesting an experiment. The two would purchase land where Washington's enslaved laborers would then work as free tenants. Lafayette believed that Washington's participation in the project would help to "render it a general practice." Lafayette hoped that his plan would prove successful in the United States and then spread out into the West Indies. While Washington replied warmly to Lafayette’s suggestion, he did not indicate a willingness to undertake a partnership in the project.

Lafayette was not to be deterred however and by June of 1785, Lafayette was ready to begin the experiment, ordering his attorney to purchase a plantation in French Guiana with the proviso that none of the enslaved people on the plantation be sold or exchanged. He intended to free the enslaved workers through gradual manumission, which he hoped would demonstrate a way to end slavery. He would outlaw the whip, grant the enslaved more free time with their families, provide them with an education, and pay them a wage – actions that Lafayette thought would prepare the enslaved for freedom. Lafayette informed Washington in February of 1786 that he had secretly acquired an estate "in order to Make that Experiment which you know is my Hobby Horse." While Washington still did not agree to be a part of the experiment, he once again replied to Lafayette saying:

"The benevolence of your heart my Dear Marquis is so conspicuous upon all occasions, that I never wonder at any fresh proofs of it; but your late purchase of an Estate in the Colony of Cayenne with a view of emancipating the slaves on it, is a generous and noble proof of your humanity. Would to God a like spirit would diffuse itself generally into the minds of the people of this country."

Lafayette’s agent in Cayenne bought two small sugar plantations in 1786. These were converted to the cultivation of spices, which required neither the back-breaking work nor deadly labor practices of sugar production. Far from acquiring a plantation to profit from the labors of the enslaved, Lafayette purchased the plantation to demonstrate to the French and all slaveholding powers a possible path toward emancipation and he was willing to spend considerable sums to do so. As Lafayette’s attentions were increasingly drawn to the unfolding revolutionary drama in France of 1789, the running of the Cayenne estates fell to his wife Adrienne. She relished the role and corresponded frequently with the estate managers as well as with the priests at a nearby seminary whom she asked to look after the religious welfare of the slaves.

The Cayenne project started slowly – the purchased lands proved unproductive, and additional land had to be purchased. Another delay occurred when the first property manager died. By 1791, however, there were 500 new clove trees under cultivation by an estimated 70 enslaved workers and family members who came with the property.

Before Lafayette’s plan could be implemented fully, however, the Revolutionary government of Robespierre ascended to power in France. Supporters of a constitutional monarchy, such as Lafayette and his family, were facing exile or death. Lafayette himself escaped France under threat of death in August of 1792, only to be imprisoned in present day Austria by royal authorities fearful that he might promote revolutionary ideas in their own country. While in prison, the Revolutionary government of France seized all his property in South America, including the enslaved workers. They would later receive formal emancipation from the French government in the mid-1790’s, only to have Napoleon Bonaparte rescind it.

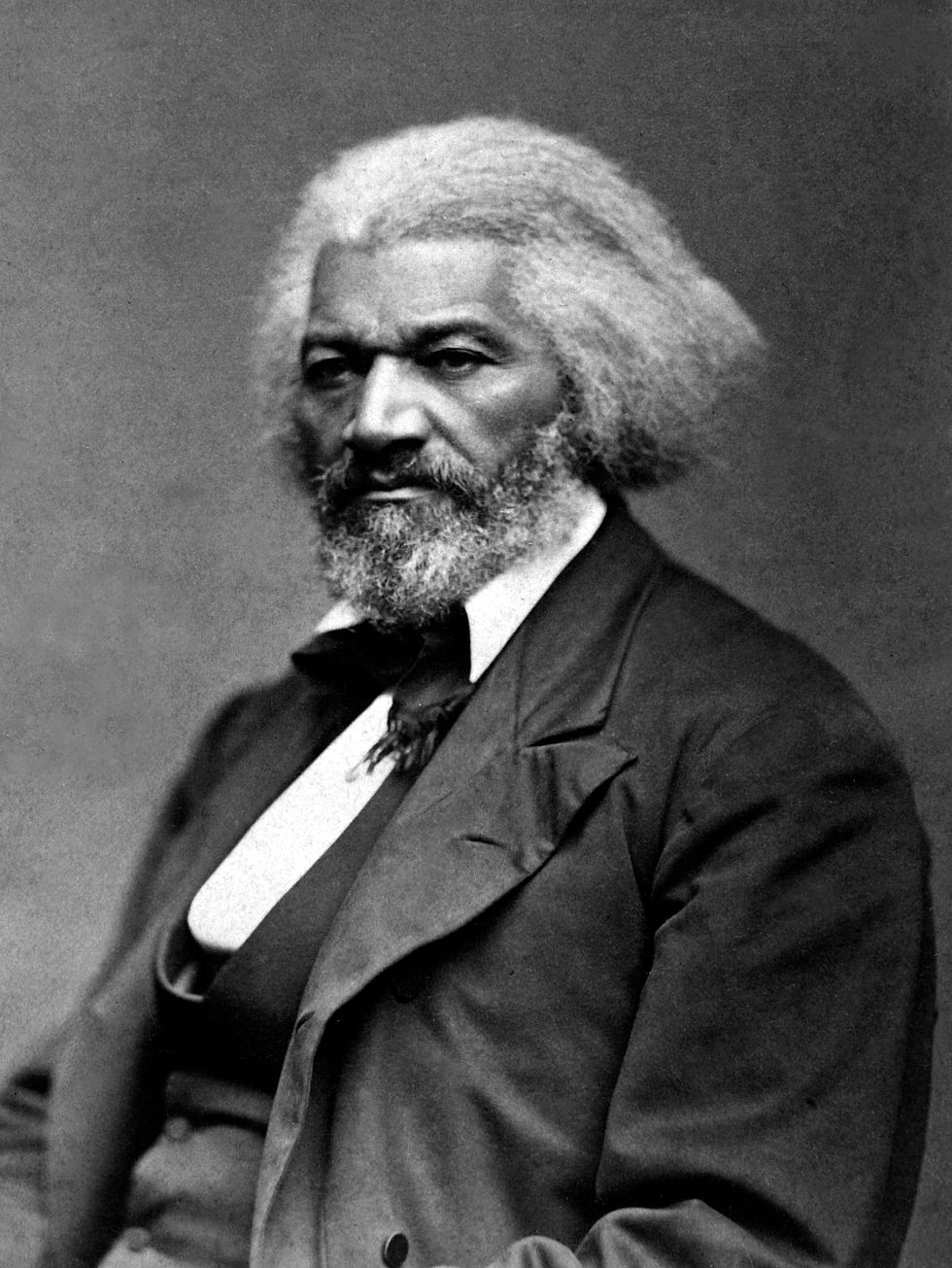

Although Lafayette’s plan for gradual manumission was never successfully implemented, he became an inspiration and a hero to black and white abolitionists such as McCune Smith in New York, Lewis Hayden and William Cooper Nell in Boston, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, and Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp in England. In his newspaper, Frederick Douglass quoted letters by George Washington praising Lafayette for the Cayenne plan. These men considered Lafayette a “true abolitionist” because he advocated for racial equality as well as emancipation.

Lafayette is one of the strongest examples of a European who rooted their abolitionism in a commitment to universal liberty and the dignity of all; in this he presents a marked contrast to certain later white abolitionists who were motivated by fears of miscegenation and who advocated a policy of deportation (“colonization”).

Long after his death, Lafayette was quoted by abolitionists in their speeches and writings in rallying northern states against compromise with the southern states on the issue using quotes such as this from a 1786 letter from Lafayette to John Adams.

“In the cause of my black brethren, I feel myself warmly interested and most decidedly side against the white part of mankind. Whatever be the complexion of the enslaved, it does not, in my opinion, alter the complexion of the crime which the enslaver commits, a crime much blacker than any African face.”

Another common quote used by abolitionists was drawn from Thomas Clarkson who said that Lafayette had told him:

“I would never have drawn my sword in the cause of America, if I could have conceived that thereby I was founding a land of slavery.”

Because Lafayette was respected and admired so greatly in America, these were powerful words that undoubtedly encouraged support for a war to free the enslaved.

Lafayette’s antislavery advocacy continued until the end of his life. During his final visit to America in 1824 and 1825, he pointedly sought out African Americans, visiting the African Free School in New York City and clasping hands with African American veterans of the War of 1812 in New Orleans, for example.

Lafayette and Human Rights

When Lafayette returned home to France, he was very enamored of his newly adopted country and the republican values he had learned there. He was determined to put them into action in France. For one thing, he desired a more representative form of government for France’s people, and he became a leading advocate for a constitutional monarchy. For another, he became an outspoken advocate for social reform in France, including Protestant freedom of religion and equal rights for all men.

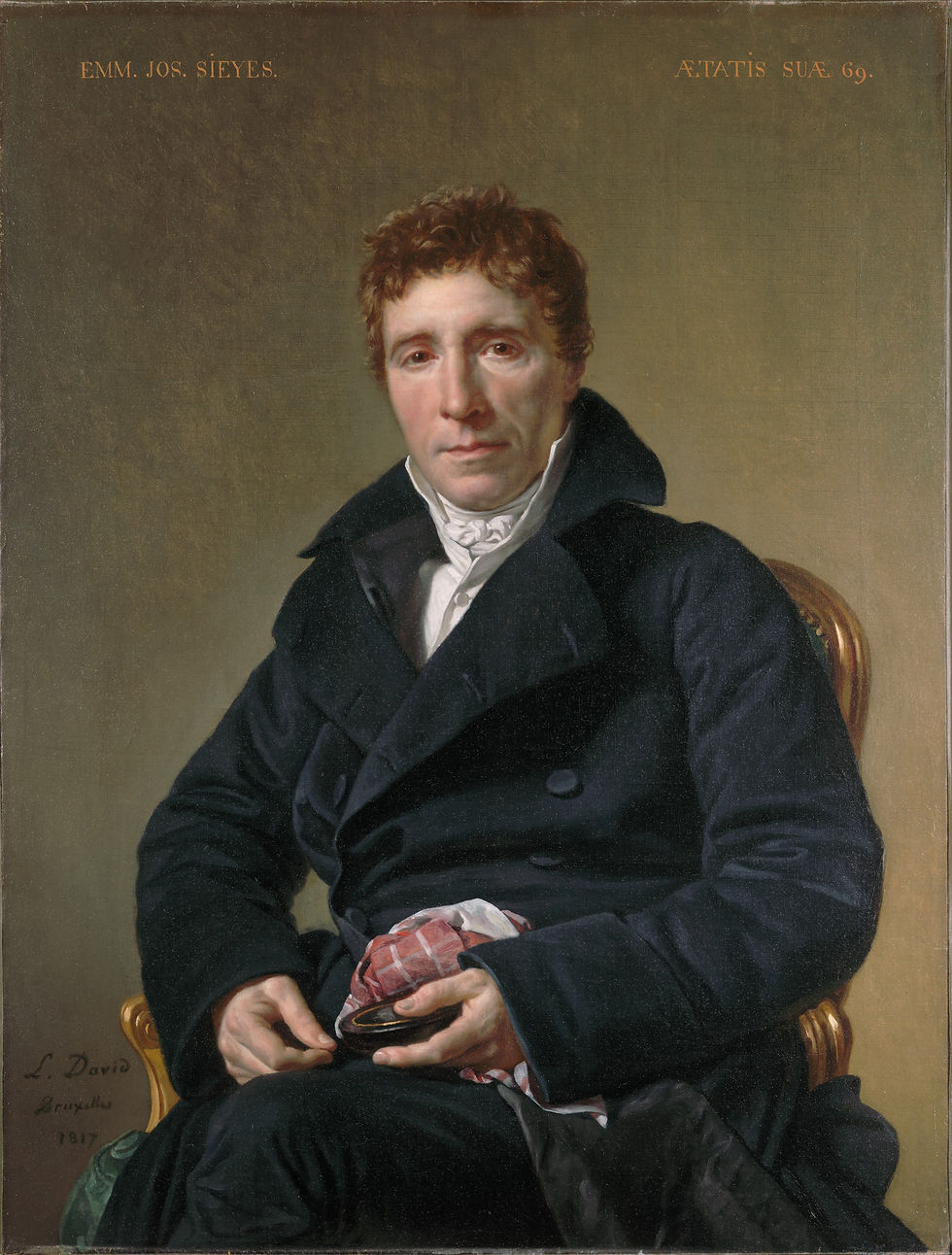

After he was elected to the National Assembly in 1789, Lafayette, with the help of Thomas Jefferson, wrote the draft for the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. However, most of the final draft came from Abbé Sieyès. Influenced by the doctrine of natural right, human rights are held to be universal: valid at all times and in every place. It became the basis for a nation of free individuals protected equally by the law.

The concepts in the Declaration come from the philosophical and political duties of The Enlightenment, such as individualism, the social contract as theorized by the philosopher Rousseau, and the separation of powers espoused by the Baron de Montesquieu. As can be seen in the texts, the French declaration was heavily influenced by the political philosophy of the Enlightenment and principles of human rights, as was the U.S. Declaration of Independence.

The Declaration defined a single set of individual and collective rights for all men. Influenced by the doctrine of natural rights, these rights are held to be universal and valid in all times and places. For example, "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good." They have certain natural rights to property, to liberty, and to life. According to this theory, the role of government is to recognize and secure these rights. Furthermore, the government should be carried on by elected representatives.[

When it was written, the rights contained in the declaration were only awarded to men. Furthermore, the declaration was a statement of vision rather than reality. The declaration was not deeply rooted in either the practice of the West or even France at the time. The declaration emerged in the late 18th century out of war and revolution, and it encountered opposition, as democracy and individual rights were frequently regarded as synonymous with anarchy and subversion. This declaration embodies ideals and aspirations towards which France pledged to struggle in the future. The following is a transcription of the articles of the Declaration:

Article I – Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

Article II – The goal of any political association is the conservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression.

Article III – The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation. No body, no individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.

Article IV – Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the fruition of these same rights. These borders can be determined only by the law.

Article V – The law has the right to forbid only actions harmful to society. Anything which is not forbidden by the law cannot be impeded, and no one can be constrained to do what it does not order.

Article VI – The law is the expression of the general will. All the citizens have the right of contributing personally or through their representatives to its formation. It must be the same for all, either that it protects, or that it punishes. All the citizens, being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents.

Article VII – No man can be accused, arrested nor detained but in the cases determined by the law, and according to the forms which it has prescribed. Those who solicit, dispatch, carry out or cause to be carried out arbitrary orders, must be punished; but any citizen called or seized under the terms of the law must obey at once; he renders himself culpable by resistance.

Article VIII – The law should establish only penalties that are strictly and evidently necessary, and no one can be punished but under a law established and promulgated before the offense and legally applied.

Article IX – Any man being presumed innocent until he is declared culpable if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, any rigor which would not be necessary for the securing of his person must be severely reprimanded by the law.

Article X – No one may be disquieted for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order established by the law.

Article XI – The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, except to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

Article XII – The guarantee of the rights of man and of the citizen necessitates a public force: this force is thus instituted for the advantage of all and not for the particular utility of those in whom it is trusted.

Article XIII – For the maintenance of the public force and for the expenditures of administration, a common contribution is indispensable; it must be equally distributed to all the citizens, according to their ability to pay.

Article XIV – Each citizen has the right to ascertain, by himself or through his representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it freely, to know the uses to which it is put, and of determining the proportion, basis, collection, and duration.

Article XV – The society has the right of requesting an account from any public agent of its administration.

Article XVI – Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured, nor the separation of powers determined, has no Constitution.

Article XVII – Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of private usage, if it is not when the public necessity, legally noted, evidently requires it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

Lafayette and Women’s Rights

In terms of his relationships with women, Lafayette was not quintessentially different from other aristocrats of his time: he dutifully accepted an early marriage of convenience, and later pursued extra-marital flirtations and friendships with “muses.” On the other hand, he also shared attitudes more typical of the bourgeoisie of the romantic era. His correspondence contains many expressions of genuine conjugal love, and reflects a lively interest in children, his own as well as those of his friends and family members.

Throughout his career as statesman, he befriended Native Americans, defended the rights of French Protestants and Jews before and during the French Revolution, backed national revolutions in Europe and South America, spoke out against capital punishment and solitary confinement. Finally, he supported women’s rights, particularly in matters like education and divorce. Although Lafayette was unable to convince the French Assembly to give women equal rights within his lifetime, his work and ideas would later become a foundational underpinning of women’s suffrage movements in the United States and Europe.

The big life lesson to take from Lafayette is to not give up the fight for human rights. Never give up the fight for justice, equality, and equity. Stay committed, even when things do not necessarily go your way, when things do not necessarily look exactly how you want them to but keep fighting for your ideals.

We hope you enjoyed today's post, “The Marquis de Lafayette: A Champion for Emancipation and Human Rights.” This is the second of three posts we will be putting up in honor of Lafayette’s October 1824 visit to the Hampton Roads region of Virginia between now and the end of October. We hope this will interest you in learning more about the Marquis de Lafayette’s role in American History. Please join us again next month as we use transcriptions of articles that appeared in late October 1824 in local newspapers to examine the celebration surrounding the Marquis de Lafayette’s visit to Hampton Roads.

Until then, while you are here on our website, we would also encourage you to join our blog community (Look for the button in the upper right-hand corner of this post). This will allow us to inform you when we post new articles. We also suggest that you return to our blog home page and sample our other articles on a wide variety of late-18th and early-19th century subjects; both military and civilian.

Finally, if you live in Virginia, Maryland, or North Carolina, we invite you to visit The Norfolk Towne Assembly’s home page to learn more about us, what we do, and how you can get involved in our historic dance, public education, and living history efforts.

References

Clarkson, T. (1846). A Letter from Thomas Clarkson. In F. O. Freedom, & M. W. Chapman (Ed.), The Liberty Bell (p. 62). Boston: Massachusetts Anti-slavery Fair.

Crawford, M. M. (1907). Madame de Lafayette and Her Family. New York: James Pott & Co.

Crow, M. F. (1927). Lafayette. Norwood, MA: Norwood Press.

Lafayette College. (2024, Sept 12). The Marquis de Lafayette. Retrieved from Lafayette: https://about.lafayette.edu/mission-and-history/the-marquis-de-lafayette/

Lafayette, M. D. (1938). Marquis de Lafayette to George Washington, 5 February 1783. In J. C. Fitzpatrick (Ed.), The Writings of George Washington (Vol. 26). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office.

L:ibertarianTVO. (2024, September 12). Marquis de Lafayette. Retrieved from Libertarianstvo Foundation: https://libertarianstvo.org/en/personalities/item/56-marquis-de-lafayette

Shaw, D., Auricchio, L., & Villers, P. (2016). A True Friend of the Cause: Lafayette and the Antislavery Movement. (O. A. Duhl, Ed.) New York: The Grolier Club.

Washington, G. (2024, August 28). From George Washington to Lafayette, 10 May 1786. Retrieved from Founders Online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-04-02-0051

Comments